A new study indicates that anxiety about social and economic collapse due to climate change is pervasive in Australia. The nationwide survey (commissioned by the author and carried out by Roy Morgan Research) reveals that nearly a third of Australians are ‘very or extremely concerned’ about social and economic collapse occurring by 2050. Three in five Australians (60 per cent) are at least moderately concerned.

Widespread acceptance of the possible breakdown of Australia’s essential systems is consistent with the proliferation of books on the subject (see, for example, the French bestseller by Pablo Servigne and Raphaël Stevens) and with the popularity of collapse podcasts such as those hosted by Sarah Wilson and Rachel Donald.

These books and podcasts turn away from the disingenuous messaging of books promising to ‘inspire’ readers with advice on ‘what you can do to help solve the climate crisis’. Instead, they offer a blunt confrontation with the actual situation, which paradoxically can permit feelings of relief. Readers no longer need to expend nervous energy on maintaining ‘hope’ in the face of the manifest reality and can actually begin to prepare themselves for life on a warmer Earth. It gives them back some agency. (This was my own unexpected reaction, as I noted in my 2010 book Requiem for a Species.)

Despite the popularity of fiction and non-fiction books about social collapse due to global warming, no one has previously tested how extensive the concern is among Australians. The survey shows that women are more worried about society collapsing than men. The difference is even wider between mothers and fathers—38 per cent of mothers are very or extremely concerned compared to 25 per cent of fathers.

That almost four in ten Australian mothers express high levels of concern about society collapsing by 2050 is worth contemplating.

There is little difference in levels of concern about collapse across age groups, which is surprising given that many younger people believe older generations are less worried about climate change. The data on levels of concern about climate change itself (analysed in Research Paper 1 in this series) confirm that age makes little difference to levels of climate concern, unlike education levels where the differences are sharp.

Before collapse

The survey also explored public concerns about: food shortages due to climate change, large numbers of climate refugees arriving, supply chain disruptions, and military conflict in our region.

Nearly a third of Australians say they are very or extremely concerned about food shortages emerging by 2050, with women substantially more worried than men. Older Australians are particularly worried about military conflict breaking out in our region under the pressure of climate change, with 45 per cent of those 60 and over saying they are very or extremely concerned compared to only 30 per cent of those under 40.

There is widespread worry about large numbers of climate refugees arriving in Australia by the middle of the century as the climate warms, with over half of the population (54 per cent) at least moderately concerned and 30 per cent very or extremely concerned.

This is perhaps the main reason the Albanese government has refused to release its report on the national security implications of the changing climate. In all likelihood, the experts who prepared the report warned that large number of boats carrying climate refugees can be expected to arrive in northern Australia in the next decades. The government would be put in an awkward position if it were asked what it is doing to prepare.

Anxieties cut across politics

What do these results tell us about how Australian society and politics may evolve? Together, they suggest that climate change has morphed in the public mind from an environmental issue into a multidimensional social challenge—one that intersects with gender divisions, national security, immigration politics, and social stability.

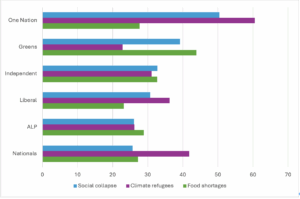

On these big questions about Australia’s future in a warming world, the differences across voting preference are less pronounced than differences over climate change itself (see the figure). Although conservative voters are much less concerned than progressive voters about climate change in general, they are, for example, substantially more concerned about the prospect of large numbers of climate refugees arriving in Australia.

In a result pregnant with implications, Greens and One Nation voters are much more worried about social collapse than Labor and Liberal Party voters. This coincidence is despite the fact that One Nation voters express very low levels of concern about climate change in general with only 16 per cent saying they are very or extremely concerned, compared to 81 per cent of Greens voters. (For comparison, 60 per cent of Labor voters say they are very or extremely concerned, while 15 per cent of Liberal Party voters and 24 per cent of National Party voters say the same)

Percentages ‘very or extremely concerned’ about social collapse, climate refugees, and food shortages by 2050, by party voted for (%)

One Nation voters’ very high level of concern about social collapse—51 per cent say they are very or extremely concerned—may be based on a sense of crisis arising from strong feelings of fear and vulnerability about social tipping points rather than ecological ones. Studies suggests that One Nation’s base is often motivated by a deep sense of cultural threat and a fear that Australian society is heading towards breakdown.

Rewiring Australia

Climate anxiety has shifted out of the activist niche and into the everyday psychology of mainstream life. The fact that 60 per cent of respondents express at least moderate concern about social collapse by 2050—a possibility at the extreme end of climate impacts—signals that climate‑related fear is now part of the collective consciousness.

This surprisingly high level of worry in the community means that future public debates, party platforms, and election campaigns will likely have to address climate anxieties and national preparedness as core voter concerns, regardless of traditional left‑right alignments. When these concerns can no longer be avoided, the divergent threat frames may push parties to craft distinct narratives, with progressives emphasizing systemic adaptation and resilience, and conservatives foregrounding border security and immigration control. Policy proposals framed around food security, health, and community stability may resonate more with women than with men, while defence and regional stability measures could find stronger support among older citizens.

Overall, with climate change now seen by Australians as intertwined with social stability, economic security, migration, and even the risk of war, the community seems to be reframing environmental threats as existential social risks. Although there’s clear evidence from the survey of collective insecurity about the future on a warming world, this sense of a precarious future in which social order and stability are no longer guaranteed is not yet part of the political discussion.

Yet this shift in assumptions about social continuity carries important implications for how citizens envision the future stability of the nation, attribute responsibility, and demand political action. Previous papers in this series have shown that they are making their own preparations for life on a warming planet—modifying their homes, shifting to safer locations and, in some cases, deciding against having children—but in the end only politics will determine which countries will do better in a warming world and which will fail.

Research Paper 7 (along with a technical report detailing the survey sampling and methodology) may be found here:

https://www.csu.edu.au/research/climate-adaptation-survey/research/research-papers

This article is published under Creative Common; it may be republished online or in print for free, provided authorship is clearly acknowledged and it is not edited, except to reflect changes in time, location, and editorial style.