Clive Hamilton & Myra Hamilton

In the game of privilege, we are all complicit. And if we are to write about privilege, we should declare our own.

We have had many advantages in life. We are both white, well-educated and well-paid, and we hail from culturally, although not materially, rich families. One of us is male. We have therefore benefited from the many unfair advantages that white middle-class Australians enjoy. It should be mentioned that we were both educated at state schools.

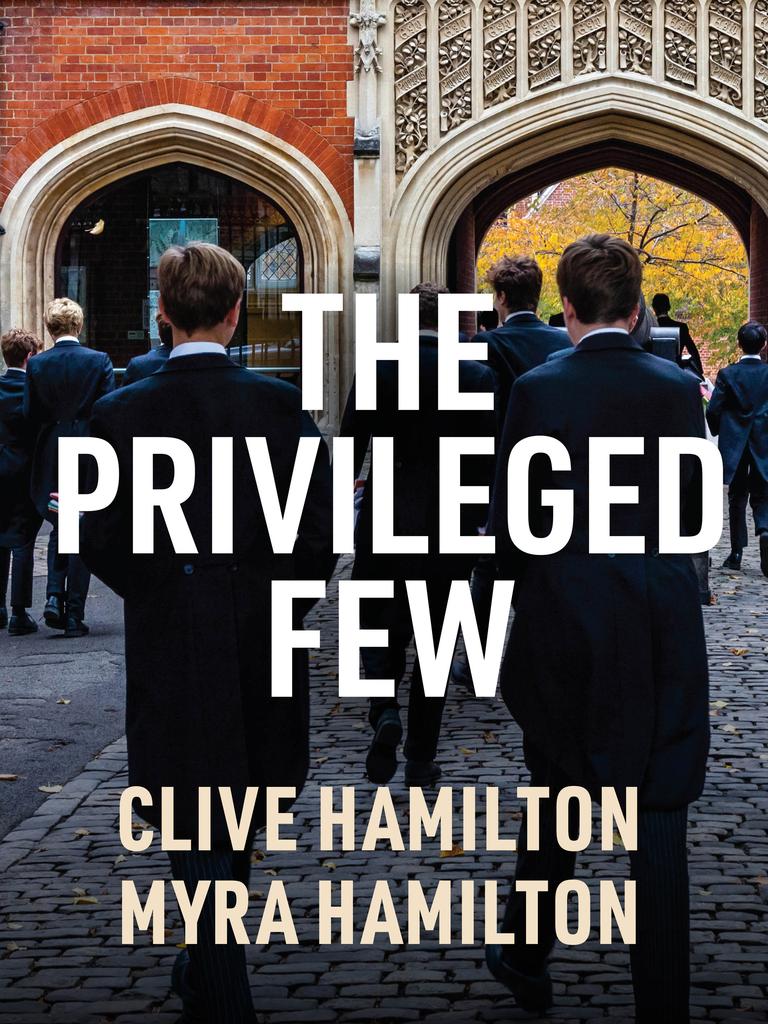

To illustrate the ways in which privilege operates in Australia, we begin with an example from private schools, because in studying privilege we found ourselves repeatedly drawn back to them.

In July 2021, Sydney was in the grip of its worst Covid-19 outbreak and struggling to cope with its highest daily caseload on record. The whole city was in lockdown: workplaces and schools were closed to all but essential workers and movement around the city was strictly limited.

The worst affected local government area was Fairfield, the city’s most disadvantaged, with extensive poverty and high levels of low-paid work in essential services such as retail, warehousing and care work. Students in the area were being schooled at home, many in situations where both parents were working and education levels were low. Home schooling was pushing many of them to breaking point.

It was a different story for children at Sydney’s elite private schools.

As experts worried that school students in Fairfield were falling further behind, students at Scots College, an exclusive private school, were permitted by the government, in an apparent exemption from the lockdown restrictions, to travel to the school’s outdoor education campus in the picturesque Kangaroo Valley for a six-month camp. There, year 9 students would undergo “a rite of passage into manhood”, according to the school’s website, a place where they would be “challenged physically, spiritually, emotionally, socially and academically”, developing in a way that “would set Scots boys apart”.

Soon after, students at the elite private school Redlands (Sydney Church of England Co-educational Grammar School, where fees for senior students are $42,000 per year) were permitted by the NSW government to travel to their Jindabyne campus, in the Snowy Mountains. Over their third term, at a cost of an additional $17,000 each, students of years 9 and 10 would combine intensive study with 11 hours a week of ski or snowboard training from qualified instructors and race coaches, opening doors for students interested in a career of competitive international snow sports.

These incidents, widely reported, soured the euphoric feeling of “we are all in this together” that had marked the opening weeks of the pandemic restrictions. It seemed to many that the veil had been lifted, revealing the ways people with privilege can bend or sidestep rules that apply to the rest of the community.

Watching this unfold prompted us to ask, “How does that work? What, in fact, is elite privilege? How is elite privilege used to evade rules?” And we wanted to understand how a privileged person signals to another that a benefit is to be granted to them and why the other responds by bestowing it.

In our book, we argue that to understand elite privilege it is not so much who elites are or what elites have that is of most interest, but the way privilege works in practice. We asked our focus group participants how they recognise privileged people. They frequently stressed disposition and personal presentation. Many referred to their bearing or, as one put it, “having a certain way about you.”

He went on: “At a function, I can pretty much work out who the key players are relatively quickly, just in the way they carry themselves, the confidence they have. They certainly have an ability to speak with a level of confidence others potentially don’t have.”

Other participants also notice the embodiment of privilege. “The way they present themselves …. I think it’s a mixture of, like, dress, job, where they live, but then also how they hold themselves … they’re usually confident and sure of themselves … The way they talk, how they conduct themselves … their body posture is a huge one.”

Some commented on “the way they walk, and the sense of entitlement people have because they’re used to a certain way of life that is already privileged. … You can spot it a mile away.”

The confidence of elites that they know the rules and can manipulate them was often on display during the pandemic lockdowns. Elites do not accept restrictions in the way others do. Elites travelled freely to their holiday homes, until a decision of the NSW “crisis cabinet” explicitly prohibited travel to holiday homes except to carry out necessary maintenance. Reports then began filtering through that wealthy Sydneysiders were travelling to their holiday homes “to mow the lawns”.

It was an instance of the way privilege is practised on a daily basis. The elites bring more resources or forms of capital to the game and have a practical mastery of it. It’s not just money but a way of understanding the system, an ease with using it to advantage that is soaked up in families and exclusive schools.

One of our focus group participants, reflecting on the networks emanating from elite schools into the top echelons of society, commented: “Even if you have the capability to solve the problem, unless you speak to the right person at the right time, in the right circles, you know you’re never going to get anywhere.”

The strategising of elite schools is matched by the strategising of the parents who send their children to them. Networks are seen as vital at a very practical level; parents enrol their children at prestigious schools so they can acquire social networks to exploit later in life. The 22,000 alumni of Wesley College keep in touch with an app, promoted as the best way to open doors and maximise the benefits of the old school network.

It’s widely believed that children who attend elite private schools have more academic success than those who attend public schools. Certainly, the schools themselves never miss an opportunity to tell the world how well their students perform in competitive examinations.

However, despite the gold-standard facilities, the small classes and the surprising ways elite schools game the system for university entrance, their students still do not outshine students from public schools once socio-economic differences are taken into account. This raises a question: if parents are paying heavily to send their children to elite schools that do not outperform public schools, what are they paying for?

We suggest that the apparent academic achievement promoted by elite private schools camouflages their true raison d’être: the transmission to the students of social, cultural and symbolic forms of capital. The networks, friendships, cultural practices, system-knowledge, disposition and status they absorb will serve them well in life beyond school and university, securing them the career breaks and financial success to which they aspire.

This is what exclusive private schools do; they consolidate and reproduce the advantages children have by being born into elite families. When elite schools, showcasing their famous alumni, promise to build character, expose students to a “unique social environment” and turn them into future leaders, these are oblique ways of promising parents that their sons and daughters will receive invaluable, and invisible, assets that public schools cannot promise and cannot deliver.

As the prime mover of the machinery of privilege, exclusive private schools are the enemy of meritocracy. They induct their charges into a special club where they are “consecrated” in the sense of being taught that they possess higher spiritual and moral qualities.

Although elite schools project an image of superior moral quality, in practice they give rise to a sense of entitlement and specialness among their students that sees many of them believing they are above society’s norms and rules. When, as is repeatedly the case, assertions of special moral character are belied by appalling episodes of moral failure, they are simply passed over as aberrations. The reputation of elite schools as superior, morally as well as academically, is enhanced by the incessant derogation of public schools, often led by the media.

In our focus groups, participants often referred to expensive private schools as “good schools”. This is only one of the ways elite schools live off state schools – beyond public funding and the draining of state schools of talented teachers, bright children and, increasingly, promising sports players. All of these further enhance the reputations of expensive private schools as the best places to send one’s children, if financially possible.

Perhaps nothing would do more to weaken the pervasive influence of elite privilege than a sharp reduction of the resourcing gap between exclusive private schools and the rest.

The children of the elites enjoy so many advantages in life that no government committed to social justice could provide any public funding for exclusive schools, including tax breaks for donations. Quite apart from the erosion of meritocratic norms, when forced in this way to subsidise these engines of elite privilege, the public suffers a moral injury.

We hope our book will prompt a robust public debate about elite privilege, allowing the subterranean rumblings of discontent to surface as social critique – in other words, for manifestations of elite privilege to be converted from private troubles into public concerns.

This is an edited extract from The Privileged Few (Polity Books) by Clive Hamilton and Myra Hamilton. It was published in The Australian on 17 May 2024

Clive Hamilton is professor of public ethics at Charles Sturt University in Canberra.

Myra Hamilton is an associate professor in Work and Organisational Studies at the University of Sydney Business School.